What is the human-like machine like?

Or, rather what it really means to be human?

We create in our own image. Or do we? The projects researched here were used by Lucy A. Suchman as examples that: ” make evident how roboticist imagine humanness”.

In the case of the human, the prevailing figuration in Euro-American imaginaries is one of autonomous, rational agency, and projects of artificial intelligence reiterate that culturally specific imaginary.

The text derives upon

Creating in our own (rational) picture?

Efforts to establish criteria of humanness (for example, tool use, language ability, symbolic representation) have always been contentious, challenged principally in terms of the capacities of other animals, particularly the nonhuman primates, to engage in various cognate behaviors.

The 3 ingredients of humanness

Lucy considers 3 elements that are “necessary for humanness” in contemporary AI projects: embodiment, emotion, and sociality. With thorough analysis, it becomes clear that the most important feature of an AI system is not its ability to discover and react to ‘classified’ emotions nor its ability to have a ‘body’ and react to space becomes, but the third feature that gives a new perspective on observing the human-like machines.

But First – Stelarc’s Prosthetic Head

This is not an illustration of disembodied intelligence. Rather, notions of awareness, identity, agency, and embodiment become problematic. Just as a physical body has been exposed as inadequate, empty and involuntary, so simultaneously the ECA becomes seductive with its uncanny simulation of real-time recognition and response. (2)

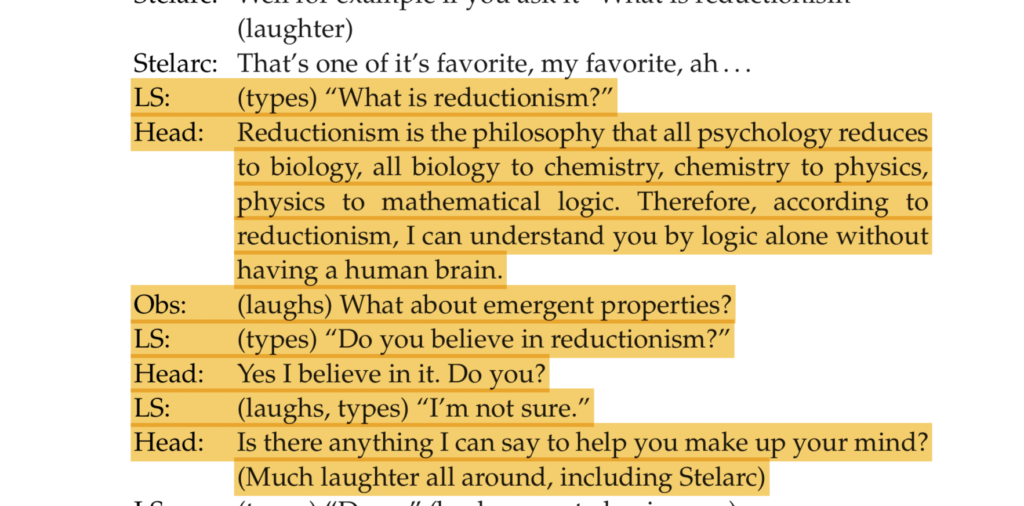

The author visited Stelarc’s exhibition in Canada in 2003 and had a valuable encounter not only with the artwork but with the author himself. What she has found to be interesting for her story is that the design of the Head was, in a sense a very human “idol” (literally – in terms of pagan rituals) of a human, its capability to anticipate the relationship in a conversation and to leave the questions “open”, and almost make a joke.

Andrew Pickering, cited by Lucy, in his book “Cybernetics and the Mangle” (2002) gives a more precise view of agency – “the liveliness” of the non-human agent or its ability to “reconfigure itself in response to its inputs”. In comparison with a lab-box-bound Kismet and its close relative Cog, if we put aside the fact that their softwares got rusty because the research stopped, the head was equipped with social skills that were far more reaching then the book of proper emotions on which the other two robots were trained at.

There is a new light in how we can observe creating new AI systems. I do not create with “me” in mind. We create with ‘us in mind – “us” socially, historically, spatially, habitually. The ‘intention’ as one of the constituents of agency is also redefined since the mind is not observed as only within one person but in terms of the relationship and cumulative historical and social map the ‘non-human’ and human belong to.

What if we understand persons as entities achieved only through the ongoing enactment of separateness. Rather

then working to create autonomous objects that mimic Cartesian subjects, we might then undertake different kinds of design projects… (3)

Following these conclusions, I have come across this intriguing example of interconnected humans and non-humans by Erin Gee: Orpheus Larynx – Vocal performance feat. Stelarc and his “Thinking Head”. Performed live at Powerhouse Museum of Technology, Sydney AU 2011.

It was an assemblage of many different ‘agents’ – a choir of 3 heads, robots and one human with a device. Erin writes on her website:

I sang along with this

avatar-choir while carrying my own silent avatar with me on a digital screen.

It is said that after Orpheus’ head was ripped from his body, he continued singing as his head floated down a river. ..The flexibility of the avatar facilitates a plurality of voices to emerge from relatively few physical bodies, blending past subjects into thepresent but also possible future subjects. Orpheus is tripled to become a multi-headed Orpheus, simultaneously disembodied head, humanoid nymph, deceased Eurydice.

Our complex humanness in many ways defined within the relationships we have to other agents and other humans. Same goes for our relationship with our ecosystem. Creating ‘in your own image’ does not mean that you are in it alone.

(1)Suchman. Lucy A, 2016, Human-Machine Reconfiguration, Cambridge University Press, UK.

(2) http://stelarc.org/

(3) Suchman. Lucy A, 2016, Human-Machine Reconfiguration, Cambridge University Press, UK.

The header image – Jordan Wolfson’s Female Figure (2014) from

More on Jordan Wolfson’s artworks https://www.davidzwirner.com/artists/jordan-wolfson